🧱Design for Manufacturing: Insights from an ex Apple, Rivian, & Tesla Leader

I interviewed an industry veteran on how he scaled physical products.

Hey Friends 🖐️,

I got the chance to talk with an industry veteran and fellow Substack author whose work I’ve admired for quite some time.

Glen Turley is a leader in engineering and manufacturing. He has developed world-class systems at Apple, Rivian, and Tesla, among others. He also teaches at the undergraduate, graduate, and executive levels.

One of the reasons I started this newsletter was to bring real-world stories into the realm of physical product-making content. The lessons from Glen’s journey are inspiring, as he offers valuable insights on how to take products from concept to mass production.

Check out Glen’s work here 👇

🤔Why Talk About Manufacturing?

I think it’s important to articulate why I chose this topic. After all, my newsletter is about hardware product management, where I typically focus more on the why, what, and who of a product rather than the how. The how, was a part of my previous life as an engineer, and there’s already great content on that topic.

But the more I write about product making, the more I realize how invaluable time on the production floor is. Especially now, especially in the age of AI.

AI has many benefits in the product development cycle. You can use it to augment product work like market research, competitive analysis, financial models, user needs studies, and even product requirement documentation. You can also use it to compress design work. You can generate block diagrams, schematics, layouts, BOMs, CAD, and even simplify factory MES systems with a single prompt. This will enable innovators to build at a pace we’ve never seen before.

But you can’t use it to replace intuition and the pain of scaling a physical product. One needs to spend time on the factory floor to see what’s actually feasible (Genba as the Japanese call it). Assembling a part, opening a mold tool, assessing fixtures, breaking components, and scaling a manufacturing line. All of these things are vital to building world-class products.

In my humble opinion, the over-reliance on AI tools may give the false perception that a demo or prototype is as good as a production-ready product. The two are very different. You cant “vibe code” your way to a robust physical product that satisfies user requirements, regulations, design intent, and quality targets.

At Tesla, Elon used to have this saying:

“Design is overrated. Manufacturing is Underrated”

In his estimation, it could be 10 to 100 times harder to design the manufacturing system than the product itself. While product design gets a lot of attention, the complex, capital-intensive process of making devices ready for mass production is less appreciated. That’s why I’m so excited to talk to Glen about his insights. Sit back and enjoy.

🎤 Interview With Glen

1. Can you talk to us about your background?

For sure, I am approaching 30 years within manufacturing both in industry and academia, split between both the UK and USA. I have been fortunate enough to work for some amazing companies including Tesla, Apple and Rivian and launching over ten products in as many years. I am now starting my next adventure as the Head of Quality Intelligence at Next-Gen Contract Manufacturer that is currently in stealth mode. Our focus is to build the first truly software-defined factory. It is a new challenge that I am incredibly excited for.

2. You’ve built world-class products at companies like Apple, Tesla, and Rivian. How were their product development cultures different?

There is actually a lot of commonality between Apple, Tesla and Rivian with regard to their product development cultures. Their focus first and foremost is to build an amazing product and if that presents manufacturing challenges, then that is something to be tackled head on and not to be avoided or mitigated for. The stories are famous of Apple Engineers being in factories in China until the small hours figuring out how to produce a complex part using a new process to exacting standards. Those tails are true both at Rivian and Tesla and I have had my fair share of long nights figuring out how to assemble or weld parts together to consistently hit precise tolerances to ensure optimum functionality.

I would say that these three companies are the exception, not the rule. They are not rigidly tied to established processes because they are constantly pushing the boundaries. If I compare them to one of my former companies JLR, who recently shutdown for six weeks because of a cyber attack, sending large swathes of the company home, putting the UK automotive supply chain at risk. This would never be allowed to happen in Silicon Valley, every part of the company would be mobilized to develop alternative processes as well as associated checks and balances to get production back up and running again in record time.

3. What are the challenges in designing products for consumer electronics vs automotive?

Yeah, here there are some differences. Starting with consumer electronics, each part is produced via precise processes, for example, the phone enclosure which is largely CNC milled with micron level precision. Due to the size of the individual components and assemblies and the quantities they are produced in, literally hitting a million phones a day at peak, 100% inspection is widely implemented throughout the supply chain so that small quantities of defects are filtered out at every stage, minimizing downstream production issues. Where this becomes challenging in design and launch is aligning quality systems with the design intent, especially for characteristics such as gaps, color, and cosmetic defects that are evaluated by industrial designers. These designers have a trained eye and your job is to align the spec, measurement system, and production process to maximize yield whilst remaining true to the industrial designers intent. This could mean binning parts so that certain distributions of spec of button color, are matched with the same distribution of enclosure cover, effectively developing a spec within a spec.

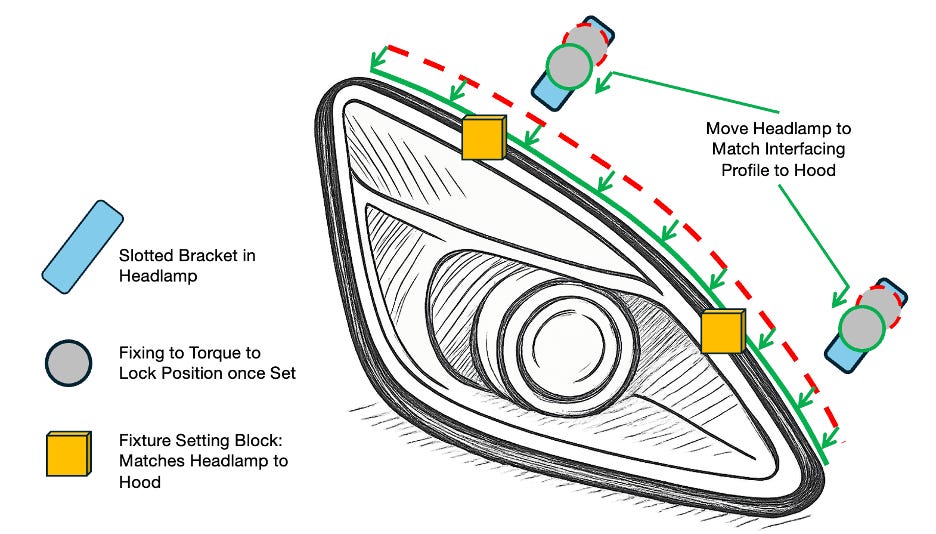

Automotive is a different beast, with the exception of the Electric Drive Unit, which is manufactured using the same precision processes as a Phone Enclosure. The other key subsystems such as battery enclosure, vehicle body or general assembly are produced using far less precise processes such as stamping, injection molding and then assembled via welding or torquing parts together in vast jigs. In addition, the vast number and size of the parts mean that the same level of quality control and defect screening simply isn’t possible. Further, because many parts are not rigid, they do not behave the way they appear on a CAD screen. All this means that individual parts may not meet their specifications, but with the right tooling, manipulation, and by shifting variation to less sensitive areas, the final product can still achieve its design intent. However, this also means there is far more debugging required in the assembly processes, and production ramp-up is much slower than in consumer electronics due to the amount of problem-solving involved.

4. What was your favorite product to work on?

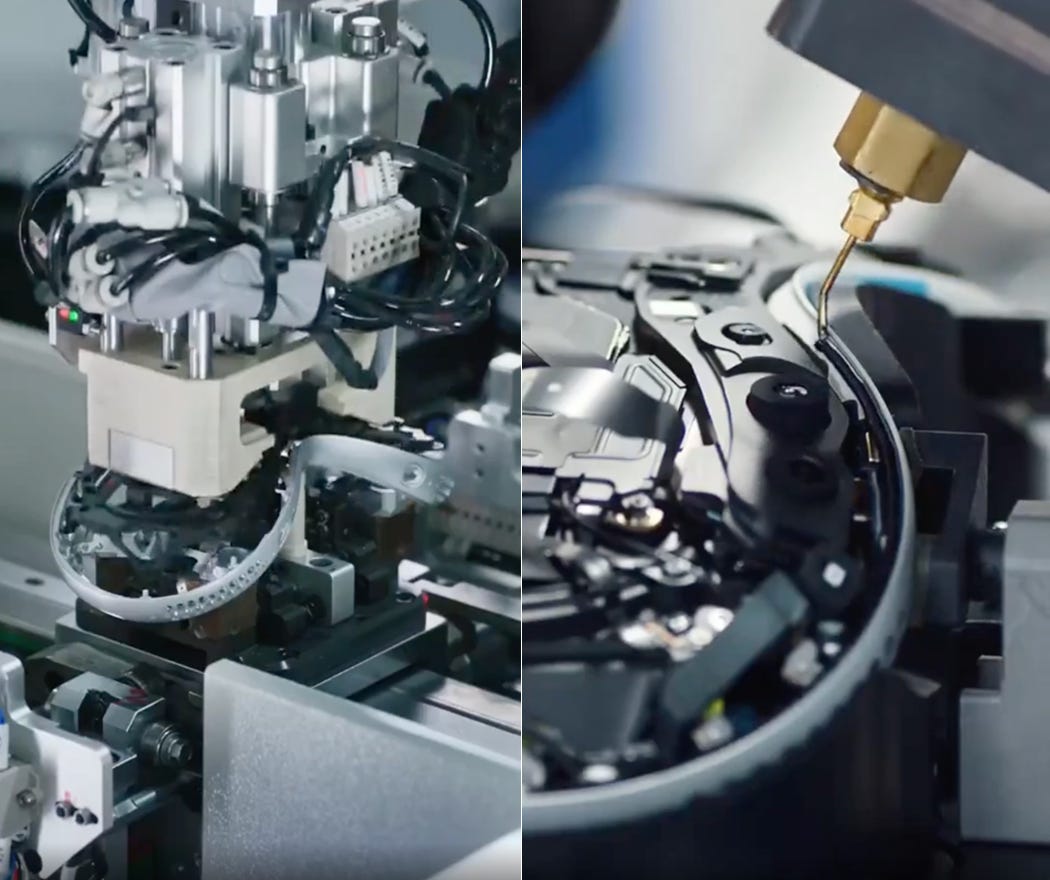

I would say there were two products that stand out. The first was the blood oxygen sensor for the Apple Watch. My background is in GD&T, tolerance analysis and metrology so this was completely new for me. While it causes stress, it is extremely rewarding to work on challenges that I have never been exposed to before. To produce a machine that could test accurately that the sensor was functioning correctly at a cycle time of a few seconds, meant not only developing the automation, but how the various LEDs and photodiodes interact to architect a valid testing methodology. The project took six months from inception, to benchtop demo, to the first mass production machine.

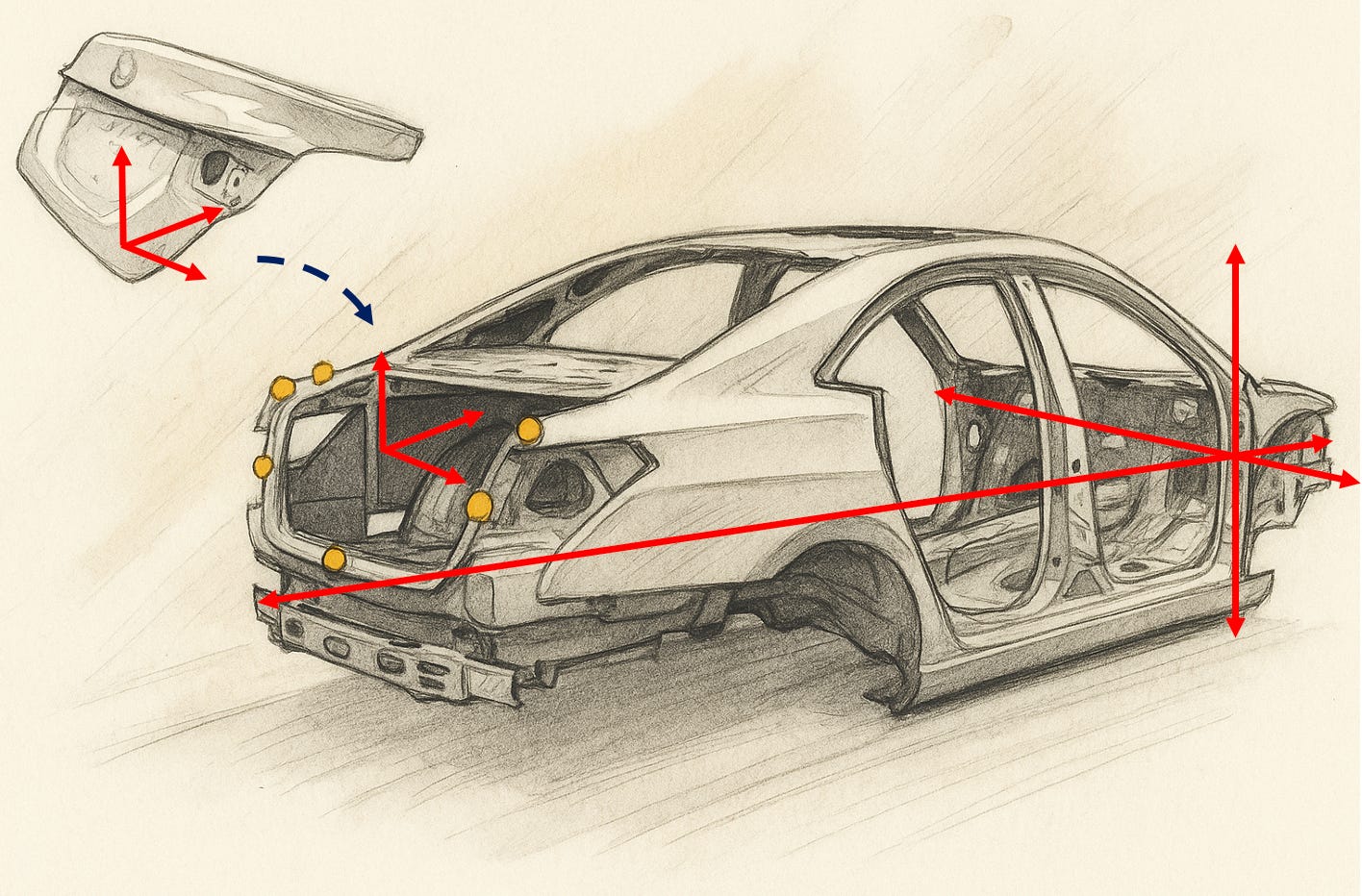

The second product was the Rivian R1S, the best SUV that is on the road today. But if you are not aware, it is manufactured on the same production line as R1T. The issue, we had launched R1T, and it needed to ramp, which meant that production was six days per week. This left only Sunday’s to commission R1S and I was in charge of Bodyshop Dimensional Accuracy, and production fixtures had not been validated from their initial design. Therefore, there was an intense period of commissioning, producing, learning, re-designing, adjusting and continual improvement over a very short intense period and we got our first sellable vehicle in a little over six months, which may sound lengthy, but this represents less than 30 commissioning days which is insane to think about it now for a completely new vehicle.

5. You’ve just finished a series on DFM. What’s design for manufacturing?

I really enjoyed writing the series on ‘Making Your Product Manufacturable’. I did not expect it to stretch over five articles. It really helped me to crystallize how design and manufacturing are inextricably linked, particularly in mass production. The engineering drawing is what binds the two together. The Designer will view it to determine if a part will function reliably once it is assembled into the final product. While the manufacturing engineer will view it from the perspective of whether their process is capable of achieving the required level of accuracy and precision to meet the tolerance specified on the drawing.

However, the engineering drawing is not a simple handover, particularly with complex assemblies there are multiple ways to achieve the required tolerance and hence functionality, which requires an intense dialogue between design and manufacturing, with regard to process sequence, datum selection and tolerance analysis to ensure the requirements of that particular are met as well as subsequent downstream processes.

6. How early in a product development process should DFM be considered?

It can be considered right when the initial surfaces of a product design are released, either through CAD visualization, or foam/clay model. It is where you as a manufacturing engineer can identify complex interfaces, which can be desensitised through the use of different strategies such as slip planes, offset surfaces, disguising interfaces or minimizing the number of parts that come together in a visually sensitive area.

However, this should not come at the expense of the product being awesome or compromising its design language. This is where Product Managers can have a key role in managing the creative tension between industrial design and manufacturing, ensuring the product brief is maintained through every DFM decision at this critical stage.

7. When is one time when DFM was ignored?

In the ‘Making Your Product Manufacturable’ series I wrote about datum transfer and ensuring that you maintain both the correct number of datums to hold the part rigid during manufacture and maintaining them as much as possible as the product progresses through the assembly process.

Well, there was one product I worked on where the number of datums the vehicle body sat on during the assembly process differed from when the doors were assembled to the vehicle, to where it went through the paint shop, and then through General Assembly. In addition, where the doors were assembled was not representative of who the vehicle sat on its tires at the end of the manufacturing process.

The end result was that the gap and flush of the doors, which is critical to how vehicle looks to the customer, changed as the vehicle process, which resulted in a series of re-fitting processes being implemented throughout the manufacturing process, until it was realized the body datum locations in the door assembly line were not supporting the body enough, resulting in sagging. Once this was found, and the expensive fix was retooling the datum locations in this line, the gap and flush through the production process became more consistent.

8. What’s your favorite manufacturing process to observe in person?

I have been fortunate to work with a number of manufacturing processes, from CNC, to injection molding, to pick and place automation. But my favorite is still the area I settled in as an apprentice back at JLR all those years back, and that is the vehicle bodyshop.

The vehicle body is the coat hanger for every part of the vehicle from cockpit, to seats, to battery enclosure and drive unit. Every part fits to it, which means it is not just about assembling the body together, it is a constant trade-off in managing the requirements of so many vehicle subsystems. In addition, it is heavily automated so seeing industrial robots manipulate and weld complete sides of cars is awesome to watch.

Further, thanks to Tesla, and now some manufacturers in China, bodyshop production is being disrupted with initiatives such as gigacastings, cell to chassis vehicle architectures and the unboxed manufacturing process, so expect further innovation in the future.

9. What’s your ideal product development process?

I think a general stage gate is good, in terms of providing a prescriptive guideline of all the activities that need to happen to bring a product to market. But it can be too rigid, and it is not good for innovation, which is more aligned to fast short iteration loops contained within sprints. Therefore, I prefer agile methodologies, which are more comfortable with multiple project changes, rather than one all-encompassing design freeze that is often idealized within stage-gate processes. However, this is difficult to achieve with hardware, because lead-times are longer, and changes need to be coordinated. If there is no coordination, then parts don’t fit together, manufacturing equipment is built to the wrong design level, etc.

Therefore, I think for complex projects, I would breakdown down stage-gate activities into a series of sprints, where changes are coordinated within these sprints, which are then tested and iterated upon within further sprint activities to allow learning and improvement. For this to be successful manufacturing equipment needs to be designed to be modular so tooling can be quickly swapped out to accommodate product and process improvements. As manufacturing becomes more software designed, I see this sprint methodology becoming more prevalent allowing for manufacturing to keep up with product technology changes.

10. What are some tips for scaling a production line from concept to mass production?

I think my biggest tip is to be social, become known to every function that your department touches. You are not an island in mass-manufacturing, the more you find out what others are doing, the earlier you can get ahead of changes coming down the line, as well as highlight potential problems and seek to address them.

Then second time around, these functions will reach out to you without prompting and learning becomes embedded, oiling the wheels of the product development cycle better than any written down process. Apple taught me this more than any other company, nothing is written down but everyone learns who they should be coordinating with, and through this coordination issues are identified and escalated early and dealt with extreme urgency.

11. Can you help people understand why scaling a HW product is harder than designing it?

No part of assembly will come out exactly like it is modelled in CAD or behave exactly as a simulation predicts. These simulations allow you to make educated manufacturing decisions, i.e. is holding a part using a certain set of datum locations, better than another set. However, educated decisions only get you so far, you need to understand how your design decisions work in practice, and this is even truer for new technologies or processes, because there are more unknowns.

The more complex the manufacturing process the more interactions, and modes of failure there are. Each one needs to be validated, and necessary controls put in to ensure that each validated production step is robust. Oftentimes, these interactions are where unexpected things happen, and require in depth problem solving, which means looking at data from upstream processes, observing production steps, to see why the product is not behaving as it does on the CAD screen.

Further, for every incremental increase in volume during ramp, new problems will arise which were previously masked by rework, longer cycle times, or by utliizing labor that now needs to be stretched thinner.

In short, manufacturing is dynamic, while CAD is static. It is a living organism and either through natural variation or because of failure in a complex chain of events, outcomes are not always predictable and it is the manufacturing engineer’s job to find out why and implement the necessary corrections to restore harmony to the system.

12. Where do you see the biggest changes in HW product design & manufacturing in the age of AI?

I think we’re entering a period where almost every piece of manufacturing software will be rewritten for the age of AI, from controls architecture to quality systems to MES. The biggest shift is that AI will finally close the gap between design and manufacturing.

Today, you can take a CAD model of a single part and automatically generate toolpaths and G-code. In the future, AI systems will do this end-to-end for full assemblies. They’ll interpret CAD together with volume targets, cost requirements, and constraints. Then break the product into a logical process sequence, define the manufacturing steps and the quality checks and even propose production equipment, robot programs, weld sequences, and controls logic.

This requires two things, Finetuned foundation models, and Structured proprietary manufacturing knowledge so the models can reason about real factory constraints. Engineers won’t disappear, they’ll be in the loop to steer outcomes, validate edge cases, and make the high-impact design decisions. But the time between a design update and factory implementation will shrink dramatically. We’ll see factories that can reconfigure in days rather than months.

13. How can young engineers and product makers break into manufacturing related roles?

Internships and Apprenticeships are invaluable here. I still think my biggest leg-up in my career was studying for my degree while I was working fulltime at JLR. It allowed me to understand manufacturing from a theoretical and practical level. Even if you want to be a Designer, and you are good with your hands if you can get a good manufacturing co-op with true responsibilities to deliver a project. This will be invaluable for your future career. You will design with a lot more awareness of the manufacturing constraints. Some designers think that if they can fit a part to a vehicle their job is done, but it needs to fit within cycle time, with the same result time after time. Having manufacturing experience is invaluable to gain knowledge of these constraints.

14. You’ve been an IC and in management. What’s some advice you have for younger professionals?

I have gone from IC to Manager and back again, changed companies in between, and I would say my way is not necessarily the best way. Engineering is broad, and to think you will find the most ideal role straight away for you to progress to management and be happy and fulfilled is slim. I would say initially don’t be afraid to try new things, and it is probably easier to transfer into different departments within the same company. It will broaden your knowledge, gain awareness of where you can have the most impact, and also where you want to develop your skills. Doing all this first, makes the transition to management easier, as you will be increasing your impact in an area where your skills and aptitude are truly aligned, allowing you to mentor engineers with a broad and deep perspective.

My final piece of career advice is, once you have the required foundational knowledge, which may come from an established company. Look for a company whose ambitions match your own, which means that your growth trajectories will be aligned. You don’t want to develop deep narrow expertise in a stagnant company where your hopes of progression are super limited. Instead, a scale-up will be hungry for both your acquired knowledge as well as your ability to learn and problem solve, and so your career will naturally scale with that company.

For more tips, follow Glen’s work here 👇

🫡 Coming Soon…

In addition to these articles, I’ve gotten requests from our community on building a course about holistic, 0→1 HW Product Management.

It’ll be a practical, end-to-end guide to taking a hardware idea from concept to mass market. I’ll be covering principles on business feasibility, go-to-market planning, user desirability, and technical viability.

My goal is to help beginners or even experienced product makers sharpen their craft. Drop your email below for 👇

For early bird pricing

Access to initial modules

Or just general interest

🙏Thanks for reading

Make sure you check out some other articles:

Amazing interview. I really loved the comparison between consumer electronics and the automotive sector, especially the process of building a "spec within a spec".

As someone who works in the auto industry, this was well worth the read! Keep em coming!

Stellar interview. The insight about AI closing the gap betwen design and manufacturing is huge, because right now that handoff is where most hardware projects stall out. What's fascinating tho is Glen's point about needing structured proprietary manufacturing knoweldge for the models to work. Sounds like companies with deep factory data and real production constraints will have a massive moat in hardware AI tooling.